It is something that's been in the back of Josiah's and my mind for months now (ever since Castle Conflict first went live in May), something that we'd intended to do a lot earlier. When we first released the game, the reviews we were getting basically said, "We love this game, but there's not enough of it!". When you have users saying, "We want more of your game!", then usually, it's a good idea to give them more of it.

All well and fair, but we felt fairly limited in what we could do. We had some significant problems, most notably, screen space; we had used up all the screen space we could, and any new units we added would require more buttons. Where would those go?

The second was, if we only have 8 units, how do we make multiple levels?

At the time, we were still of the mindset that iPhone games would not take us long to make. Castle Conflict had taken us 1 day of prototyping + 8 days developing + 1 day finalising. And those weren't full days. Furthermore, we had an idea for another game that we thought would not take long to make: Ant Attack. Surely, if we made Castle Conflict in a week, we could make Ant Attack in one, maybe two? And during that week, we could let our subconcious work on ideas for how to fix Castle Conflict. Surely, our users could wait a week for another update?

That ended up not being the case. The truth is, we don't work together full-time. I had a couple of computer games I was finishing up at the time. Josiah is also working on a computer game and a band project. To make matters further delayed, we each had a summer vacation of greater than one week planned, but neither of us at the same time.

Ant Attack ended up taking us 4 weeks of development, but because of our varied schedules, did not get released until the middle of October, at which point I was in the midst of a move. So it is with a huge sigh of relief that we were able to sit down, solve the aforementioned problems of Castle Conflict, and free a block of time to finish it.

Let this be a lesson to all future iPhone developers: Make your update for your game as soon as possible! What we should have thought in May, and will think next time, is "Surely this audience who might want Ant Attack can wait a week until our existing audience is pleased with the update they have told us they want." Because, you don't know how often those weeks of productivity are going to be available to you. And you want to address the audience that already exists, not one that might not.

What update?

In order for this to be feasible in the time we have available (once again, just one week), we are once again structuring this update in a tiered manner, and those tiers are:

1) Campaign Mode, New unit pack 1

2) Quick Play Cleanup

3) Campaign Mode Cleanup

4) New Unit Pack 2

5) New Unit Pack 3

6) Multiplayer

Sadly, multiplayer is last, and we don't really expect to get it in this update, as much as we would like to. Luckily, updating is easy to do.

Planning is Key!

We have one week for this project, so once again, we are using as many productivity tools as possible to keep things organised and moving smoothly.

1) MSN: We are working from different cities, so the ability to communicate in real time is a huge need. MSN allows us to do that.

2) XP-Dev: We are once again using this online tool to manage our tasks and plan our project. The software has been updated, so before where we had to rank our tasks by integral values to determine their importance, this time we were able to split our tasks across multiple iterations, as outline above.

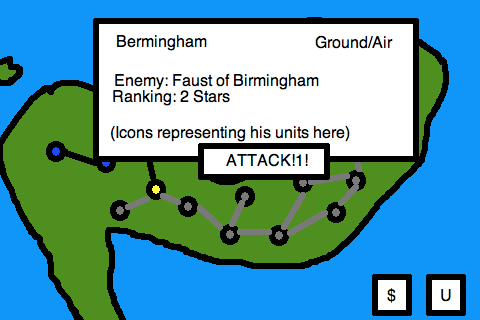

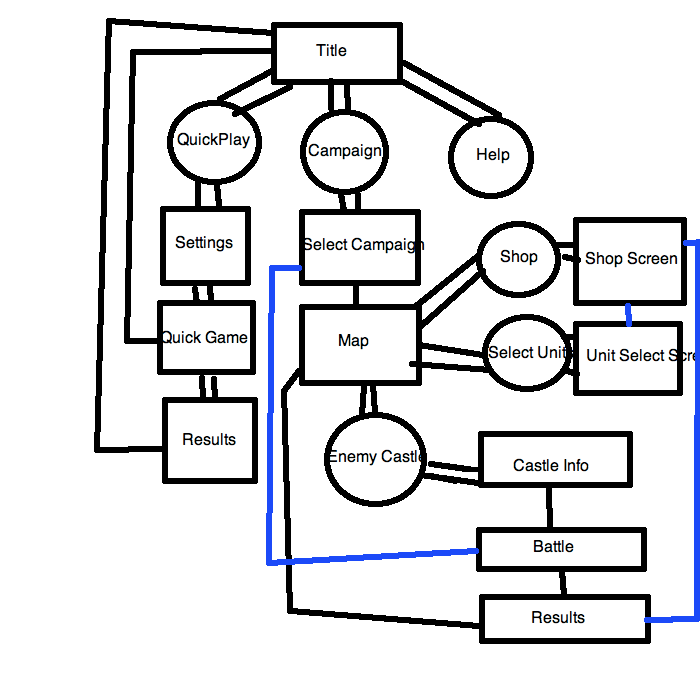

3) Mockups/Flow charts: Okay, so we are very 'indy', and I use the free Mac 'Paintbrush' software to make these, so they don't look as professional as those done in Visio or another equivalent software. Nonetheless, sometimes the best way to communicate is visually, so we use images as below to communicate ideas before spending hours working on implementation and graphics for them: